By Stuart Mitchner

In an interview in this Sunday’s New York Times, the actor Ed Helms (The Office) says his favorite reading experience took place on the subway, clinging to a pole with one hand and reading Moby-Dick on his cell phone with the other. It’s a connection that might have amused Herman Melville, who was riding the elevated subway to and from his job as a customs inspector until his retirement in 1886, five years before his death. I wish he were around to write a response to D.H. Lawrence’s wildly conflicted tribute to the “deep great artist” who wrote Moby-Dick, “a very great book” that “commands a stillness in the soul, an awe” that Lawrence found hard to match with the author, a “rather tiresome New Englander” — “Oh dear, when the solemn ass brays! brays! brays!”

In an interview in this Sunday’s New York Times, the actor Ed Helms (The Office) says his favorite reading experience took place on the subway, clinging to a pole with one hand and reading Moby-Dick on his cell phone with the other. It’s a connection that might have amused Herman Melville, who was riding the elevated subway to and from his job as a customs inspector until his retirement in 1886, five years before his death. I wish he were around to write a response to D.H. Lawrence’s wildly conflicted tribute to the “deep great artist” who wrote Moby-Dick, “a very great book” that “commands a stillness in the soul, an awe” that Lawrence found hard to match with the author, a “rather tiresome New Englander” — “Oh dear, when the solemn ass brays! brays! brays!”

My guess is that besides savoring words of praise from a brilliant colleague, a man with Melville’s wonderfully inventive sense of humor would laugh at the “solemn ass,” and, if it were possible, post Lawrence a copy of his sketch “Cock-a-Doodle-Doo!” about “the loudest, longest, and most strangely musical crow that ever amazed mortal man…. a wise crow; an invincible crow; a philosophic crow; a crow of all crows.” more

On the night of October 15, 1956, viewers of I Love Lucy, the nation’s most popular television show, saw Lucille Ball and Orson Welles doing a scene from Romeo and Juliet. Welles has his doubts, but she’s been showering him with compliments, telling him he’s better than John Gielgud, Maurice Evans, Sir Ralph Richardson, and, after he prompts her, Laurence Olivier. Looking like an adult parody of her Peanuts namesake, Lucy delivers her jawbreaker of a line with outstretched arms, “What man art thou that, thus bescreened in night, so stumblest on my counsel?”

On the night of October 15, 1956, viewers of I Love Lucy, the nation’s most popular television show, saw Lucille Ball and Orson Welles doing a scene from Romeo and Juliet. Welles has his doubts, but she’s been showering him with compliments, telling him he’s better than John Gielgud, Maurice Evans, Sir Ralph Richardson, and, after he prompts her, Laurence Olivier. Looking like an adult parody of her Peanuts namesake, Lucy delivers her jawbreaker of a line with outstretched arms, “What man art thou that, thus bescreened in night, so stumblest on my counsel?”

I’ve always been interested in poetry and poets that show up in unexpected places. And, as happened recently with another national recognition month, I’d forgotten that April was National Poetry Month. Even so, given my sense of poetry as a gift not necessarily confined between the covers of a book, I inadvertently signaled the subject this month with pieces featuring a great poet named Charlie Chaplin (who W.C. Fields, a poet himself, called a “ballerina”); a lesser known “disappearing” poet (Weldon Kees); and the greatest of them all, on the stage or the page or in the air, William Shakespeare. The one sentence of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s I know by heart is from his essay “The Poet”: “The people fancy they hate poetry, and they are all poets and mystics.”

I’ve always been interested in poetry and poets that show up in unexpected places. And, as happened recently with another national recognition month, I’d forgotten that April was National Poetry Month. Even so, given my sense of poetry as a gift not necessarily confined between the covers of a book, I inadvertently signaled the subject this month with pieces featuring a great poet named Charlie Chaplin (who W.C. Fields, a poet himself, called a “ballerina”); a lesser known “disappearing” poet (Weldon Kees); and the greatest of them all, on the stage or the page or in the air, William Shakespeare. The one sentence of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s I know by heart is from his essay “The Poet”: “The people fancy they hate poetry, and they are all poets and mystics.” Even before I read about those advertisements in Edward Tenner’s new book Why the Hindenburg Had a Smoking Lounge: Essays on Unintended Consequences (American Philosophical Society Press $34.95), my interest in vintage cigarette ads had been stirred by a Broadhurst Theatre Playbill from 1934, three years before May 6, 1937, the day the Hindenburg crashed and burned on landing at Lakehurst N.J. Naval Air Station, killing 35 of the 97 passengers. By specifying the proportion of fatalities, Tenner leaves it up to us to assume that most of the victims were in the smoking lounge at the time (“under 7 million cubic feet of flammable gas”), a possibility underscored by a pointed reference to satirist Bruce McCall’s drawing of a Hindenburg prospectus showing a skeleton in an officer’s uniform asking elegant passengers, “Zigarette?”

Even before I read about those advertisements in Edward Tenner’s new book Why the Hindenburg Had a Smoking Lounge: Essays on Unintended Consequences (American Philosophical Society Press $34.95), my interest in vintage cigarette ads had been stirred by a Broadhurst Theatre Playbill from 1934, three years before May 6, 1937, the day the Hindenburg crashed and burned on landing at Lakehurst N.J. Naval Air Station, killing 35 of the 97 passengers. By specifying the proportion of fatalities, Tenner leaves it up to us to assume that most of the victims were in the smoking lounge at the time (“under 7 million cubic feet of flammable gas”), a possibility underscored by a pointed reference to satirist Bruce McCall’s drawing of a Hindenburg prospectus showing a skeleton in an officer’s uniform asking elegant passengers, “Zigarette?” I’d agree with Agee if I hadn’t just seen Fields at his flinching, cringing, fumbling, pugnacious, masterfully disoriented best in the 1926 silent The Old Army Game, which also offered actual visual details (cars, stores, streets, small town America) to compare to the period recreation in Paramount’s recent series 1923. Given Chaplin’s immense popularity in those days, it was interesting to watch his 1923 silent feature The Pilgrim alongside Taylor Sheridan’s brilliant prequel to Yellowstone at a time when theaters all over the country, including one in Billings, Montana, would have been screening the latest Chaplin. And since The Pilgrim opened in New York in late February 1923, I’m taking the liberty of installing it in a Times Square movie house on the day that 1923’s embattled heroine Alexandra Dutton arrived in America.

I’d agree with Agee if I hadn’t just seen Fields at his flinching, cringing, fumbling, pugnacious, masterfully disoriented best in the 1926 silent The Old Army Game, which also offered actual visual details (cars, stores, streets, small town America) to compare to the period recreation in Paramount’s recent series 1923. Given Chaplin’s immense popularity in those days, it was interesting to watch his 1923 silent feature The Pilgrim alongside Taylor Sheridan’s brilliant prequel to Yellowstone at a time when theaters all over the country, including one in Billings, Montana, would have been screening the latest Chaplin. And since The Pilgrim opened in New York in late February 1923, I’m taking the liberty of installing it in a Times Square movie house on the day that 1923’s embattled heroine Alexandra Dutton arrived in America. Born April 9, 1806, British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel once claimed that the “most wonderful feat” he ever performed was producing “unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject — taste.” He was referring to the panel of experts that approved his ambitious design for the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, the longest in the world at the time of its construction in 1831.

Born April 9, 1806, British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel once claimed that the “most wonderful feat” he ever performed was producing “unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject — taste.” He was referring to the panel of experts that approved his ambitious design for the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, the longest in the world at the time of its construction in 1831. Mexico’s Mysterious Stranger” is the way James Agee characterized B. Traven in his February 2, 1948 Time review of John Huston’s film adaptation of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I’ve been haunted by Traven’s multi-faceted invisibility ever since last week’s column on the “disappearing poet” Weldon Kees, who told a friend in his last phone call in May 1955: “I may go to Mexico. To stay.” My interest in Traven began in earnest on Albert Einstein’s birthday, March 14, Pi Day in Princeton, after hearing that Traven’s The Death Ship (Das Totenschiff), published in German in 1926, is the novel Einstein named when asked what book he’d take to a desert island.

Mexico’s Mysterious Stranger” is the way James Agee characterized B. Traven in his February 2, 1948 Time review of John Huston’s film adaptation of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I’ve been haunted by Traven’s multi-faceted invisibility ever since last week’s column on the “disappearing poet” Weldon Kees, who told a friend in his last phone call in May 1955: “I may go to Mexico. To stay.” My interest in Traven began in earnest on Albert Einstein’s birthday, March 14, Pi Day in Princeton, after hearing that Traven’s The Death Ship (Das Totenschiff), published in German in 1926, is the novel Einstein named when asked what book he’d take to a desert island. I was on my way out of the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Preview Sale with $10 worth of books when I noticed a devastated Cedok guide to Prague on a table of discards. Although the back cover was detached, the book was full of information and photos from a time when Franz Kafka and his family were living in the Czech capital. Attached to the ravaged back cover was a large colorful fold-out map of Prague in first-rate condition, which I’ve been using to locate entries from Kafka’s Diaries 1910-1923 (Schocken 1975).

I was on my way out of the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Preview Sale with $10 worth of books when I noticed a devastated Cedok guide to Prague on a table of discards. Although the back cover was detached, the book was full of information and photos from a time when Franz Kafka and his family were living in the Czech capital. Attached to the ravaged back cover was a large colorful fold-out map of Prague in first-rate condition, which I’ve been using to locate entries from Kafka’s Diaries 1910-1923 (Schocken 1975). A few days ago I listened to Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra’s performance of Sergei Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony and have been buoyed by the joyous ambiance of this 13 minutes of music ever since. In the colorful image accompanying the piece on YouTube, Prokofiev is lounging on a cane chair surrounded by greenery, one leg casually balanced on the other, one arm slung over the back of the chair, holding a score he’s been working on, a pencil in his other hand. He’s dressed casually in a dark brown zippered jacket, and he’s looking good, touches of color in his cheeks, no glasses, in his thirties or forties, prime of life, and as in other photos from this period (see his wikipedia page), he looks more like a Russian David Bowie than the generic image of the severe, bespectacled composer.

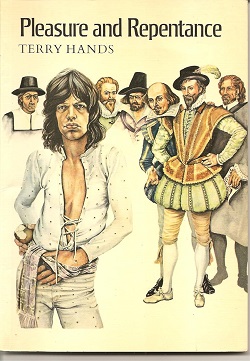

A few days ago I listened to Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra’s performance of Sergei Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony and have been buoyed by the joyous ambiance of this 13 minutes of music ever since. In the colorful image accompanying the piece on YouTube, Prokofiev is lounging on a cane chair surrounded by greenery, one leg casually balanced on the other, one arm slung over the back of the chair, holding a score he’s been working on, a pencil in his other hand. He’s dressed casually in a dark brown zippered jacket, and he’s looking good, touches of color in his cheeks, no glasses, in his thirties or forties, prime of life, and as in other photos from this period (see his wikipedia page), he looks more like a Russian David Bowie than the generic image of the severe, bespectacled composer. Raleigh’s poem “A Description of Love” begins and ends Pleasure and Repentance (Pergamon 1976), the Royal Shakespeare Company’s “Lighthearted Look at Love” created and compiled by former RSC Director Terry Hands. The subject of acting and actors, love and lovers brings to mind Sunday night’s Academy Awards, where Morgan Freeman delivered a memorial tribute to Gene Hackman (“Our community lost a giant, I lost a dear friend”) and four Oscars went to Sean Baker’s Anora, a zany throwback to the screwball comedy romances of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Raleigh’s poem “A Description of Love” begins and ends Pleasure and Repentance (Pergamon 1976), the Royal Shakespeare Company’s “Lighthearted Look at Love” created and compiled by former RSC Director Terry Hands. The subject of acting and actors, love and lovers brings to mind Sunday night’s Academy Awards, where Morgan Freeman delivered a memorial tribute to Gene Hackman (“Our community lost a giant, I lost a dear friend”) and four Oscars went to Sean Baker’s Anora, a zany throwback to the screwball comedy romances of Hollywood’s Golden Age. When I realized last Saturday was George Washington’s birthday, I looked up former president Bill Clinton’s foreword to Shakespeare in America (Library of America 2013), which refers to Washington leaving the “legislative haggling” at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to see a production of The Tempest, which, as editor James Shapiro points out, was “based on the story of the wreck of the Sea Venture off the coast of Bermuda in 1609.” The 42nd president — who remembers a high school assignment requiring him to memorize 100 lines from Macbeth, among them “Life’s but a walking shadow” (“an important early lesson in the perils of blind ambition”) — makes sure to mention the time presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson visited Stratford-upon-Avon. Later in the book, as Abigail Adams recalls, Jefferson “fell upon the ground and kissed it” while Adams “cut a relic from a chair claimed to have belonged to Shakespeare himself.”

When I realized last Saturday was George Washington’s birthday, I looked up former president Bill Clinton’s foreword to Shakespeare in America (Library of America 2013), which refers to Washington leaving the “legislative haggling” at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to see a production of The Tempest, which, as editor James Shapiro points out, was “based on the story of the wreck of the Sea Venture off the coast of Bermuda in 1609.” The 42nd president — who remembers a high school assignment requiring him to memorize 100 lines from Macbeth, among them “Life’s but a walking shadow” (“an important early lesson in the perils of blind ambition”) — makes sure to mention the time presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson visited Stratford-upon-Avon. Later in the book, as Abigail Adams recalls, Jefferson “fell upon the ground and kissed it” while Adams “cut a relic from a chair claimed to have belonged to Shakespeare himself.” When John Keats wrote about life and love to Fanny Brawne, he had less than a year to live. In a letter from Rome on November 30, 1820, his last, he told his friend Charles Brown, “There is one thought enough to kill me; I have been well, healthy, alert, &c., walking with her, and now — the knowledge of contrast, feeling for light and shade, all that information (primitive sense) necessary for a poem, are great enemies to the recovery of my stomach.”

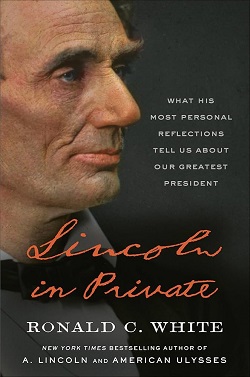

When John Keats wrote about life and love to Fanny Brawne, he had less than a year to live. In a letter from Rome on November 30, 1820, his last, he told his friend Charles Brown, “There is one thought enough to kill me; I have been well, healthy, alert, &c., walking with her, and now — the knowledge of contrast, feeling for light and shade, all that information (primitive sense) necessary for a poem, are great enemies to the recovery of my stomach.” Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect.” With these words the poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg began his address to a joint session of Congress on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, February 12, 1959.

Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect.” With these words the poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg began his address to a joint session of Congress on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, February 12, 1959. The finale to Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, based on his song “Der Wanderer,” has been described as “technically transcendental” with a “thunderous” conclusion. It was also infamously difficult to play, so deviously demanding that Schubert himself reportedly threw up his hands during a recital and yelled “Let the devil play it!”

The finale to Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, based on his song “Der Wanderer,” has been described as “technically transcendental” with a “thunderous” conclusion. It was also infamously difficult to play, so deviously demanding that Schubert himself reportedly threw up his hands during a recital and yelled “Let the devil play it!” Bob Dylan put President McKinley back in the national consciousness a few years ago in his song “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” taking the first line from Charlie McCoy’s “White House Blues,” except in McCoy’s version the second line was “Doc said to McKinley, ‘I can’t find that ball,’ “ meaning the second of two bullets fired at close range into the president’s abdomen on September 6, 1901. It happened at the Temple of Music on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. McKinley died on September 14, 1901, a hundred years to the week of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center.

Bob Dylan put President McKinley back in the national consciousness a few years ago in his song “Key West (Philosopher Pirate),” taking the first line from Charlie McCoy’s “White House Blues,” except in McCoy’s version the second line was “Doc said to McKinley, ‘I can’t find that ball,’ “ meaning the second of two bullets fired at close range into the president’s abdomen on September 6, 1901. It happened at the Temple of Music on the grounds of the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. McKinley died on September 14, 1901, a hundred years to the week of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center. If David Lynch were still delivering daily weather reports on his YouTube channel, and if he’d lived to see Inauguration Day, his January 20 forecast would have ended with his usual cheery, heartfelt “golden sunshine and blue skies all the way” closing line, topped off with a smile and a vigorous salute, regardless of the actual weather in L.A. or D.C. Unfortunately, actual earthly weather in the form of the Santa Ana winds driving the wildfires devastating his city forced the mandatory evacuation of Lynch’s home on the night of Wednesday, January 8. The timing and the circumstances were, as some online bloggers have noted, “Lynchian.” Not only was the director of Mulholland Drive living adjacent to the street that gave his most celebrated film its title, he was homebound, seriously ill with emphysema, and in need of “supplemental oxygen for most activities.” Even though the evacuation order was rescinded the next morning, the damage had apparently been done. Less than a week later, Lynch’s family announced his January 15 death.

If David Lynch were still delivering daily weather reports on his YouTube channel, and if he’d lived to see Inauguration Day, his January 20 forecast would have ended with his usual cheery, heartfelt “golden sunshine and blue skies all the way” closing line, topped off with a smile and a vigorous salute, regardless of the actual weather in L.A. or D.C. Unfortunately, actual earthly weather in the form of the Santa Ana winds driving the wildfires devastating his city forced the mandatory evacuation of Lynch’s home on the night of Wednesday, January 8. The timing and the circumstances were, as some online bloggers have noted, “Lynchian.” Not only was the director of Mulholland Drive living adjacent to the street that gave his most celebrated film its title, he was homebound, seriously ill with emphysema, and in need of “supplemental oxygen for most activities.” Even though the evacuation order was rescinded the next morning, the damage had apparently been done. Less than a week later, Lynch’s family announced his January 15 death. Blowing through the buttons of our coats / Blowing through the letters that we wrote / Idiot wind / Blowing through the dust upon our shelves….” The next lines, and the last, of Bob Dylan’s song are “We’re idiots, babe / It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves.”

Blowing through the buttons of our coats / Blowing through the letters that we wrote / Idiot wind / Blowing through the dust upon our shelves….” The next lines, and the last, of Bob Dylan’s song are “We’re idiots, babe / It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves.” I woke up from a nap five minutes before midnight, turned on the TV, and there was Times Square packed with Happy 2025-top-hatted, rainwear-cloaked revelers under a delirium of color that swarmed into futuristic formations every time I blinked my eyes. At first the signs were meaningless, nameless, wordless, New Year’s Eve on Mars, like a vision of the place I loved as a 14-year-old seen through the eyes of old Rip Van Winkle emerging from a showing of A Star Is Born on a rainy night in 1954. What does it mean, all this dazzling stuff? Where’s a familiar face? Where’s Judy Garland? Where’s any legible meaningful remnant of lost New York? Then, wonder of wonders, a floodlit sign for The Great Gatsby comes into view on the first day of the novel’s 100th year, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is in lights, and Broadway makes 20th-century sense again….

I woke up from a nap five minutes before midnight, turned on the TV, and there was Times Square packed with Happy 2025-top-hatted, rainwear-cloaked revelers under a delirium of color that swarmed into futuristic formations every time I blinked my eyes. At first the signs were meaningless, nameless, wordless, New Year’s Eve on Mars, like a vision of the place I loved as a 14-year-old seen through the eyes of old Rip Van Winkle emerging from a showing of A Star Is Born on a rainy night in 1954. What does it mean, all this dazzling stuff? Where’s a familiar face? Where’s Judy Garland? Where’s any legible meaningful remnant of lost New York? Then, wonder of wonders, a floodlit sign for The Great Gatsby comes into view on the first day of the novel’s 100th year, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece is in lights, and Broadway makes 20th-century sense again….

My preferred Santa of the moment is the one trudging up the Union Square subway stairs on the cover of the December 16 New Yorker, a heavy red bag slung over his shoulder, one hand on the railing, snow falling. I like the noirish urban darkness of Eric Drooker’s image, the way the Con Ed building is framed, the fading portrait of a beloved city against a blank sky. I also like the touch of mortal menace. Will Santa make it to his next stop before he’s mugged or run down by a drunken driver?

My preferred Santa of the moment is the one trudging up the Union Square subway stairs on the cover of the December 16 New Yorker, a heavy red bag slung over his shoulder, one hand on the railing, snow falling. I like the noirish urban darkness of Eric Drooker’s image, the way the Con Ed building is framed, the fading portrait of a beloved city against a blank sky. I also like the touch of mortal menace. Will Santa make it to his next stop before he’s mugged or run down by a drunken driver? According to A Book of Days for the Literary Year, the week of December 15 begins with the publication of Emma, a day before Jane Austen’s 40th birthday in 1815. Emma Woodhouse’s comment about a divided understanding of the world’s pleasures, spoken soon after she herself disastrously misunderstands a courtship charade, has me thinking about Authors, the card game that my parents and I played when I was a boy. The fact that Jane Austen had been overlooked by the creators of the game (the only female being Louisa May Alcott) naturally didn’t occur to me, although when my wife and I played Authors with our son decades later, her absence was front and center. How could they leave her out, a question that had serious resonance on the Christmas morning I gave my wife illustrated editions of Persuasion and Mansfield Park.

According to A Book of Days for the Literary Year, the week of December 15 begins with the publication of Emma, a day before Jane Austen’s 40th birthday in 1815. Emma Woodhouse’s comment about a divided understanding of the world’s pleasures, spoken soon after she herself disastrously misunderstands a courtship charade, has me thinking about Authors, the card game that my parents and I played when I was a boy. The fact that Jane Austen had been overlooked by the creators of the game (the only female being Louisa May Alcott) naturally didn’t occur to me, although when my wife and I played Authors with our son decades later, her absence was front and center. How could they leave her out, a question that had serious resonance on the Christmas morning I gave my wife illustrated editions of Persuasion and Mansfield Park.  In the opening sentence of Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel Amerika (New Directions), the Statue of Liberty is holding aloft a sword instead of a torch. There are disputes online about whether this was unintended or intentional. Not to worry. With a writer as infinitely suggestive as Kafka, errors can have prophetic consequences, and since he has, in effect, arrived in post-election America for a centenary exhibit at the Morgan Library & Museum, some interesting connections are already in play, notably Barry Blitt’s New Yorker cover depicting a very nervous, verge-of-vertigo Lady Liberty walking a tightrope.

In the opening sentence of Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel Amerika (New Directions), the Statue of Liberty is holding aloft a sword instead of a torch. There are disputes online about whether this was unintended or intentional. Not to worry. With a writer as infinitely suggestive as Kafka, errors can have prophetic consequences, and since he has, in effect, arrived in post-election America for a centenary exhibit at the Morgan Library & Museum, some interesting connections are already in play, notably Barry Blitt’s New Yorker cover depicting a very nervous, verge-of-vertigo Lady Liberty walking a tightrope. The epigraph comes by way of the first Arts page in Monday’s New York Times. At least once or twice every year, the Newspaper of Record throws out a line that hooks me. Picture a Dr. Seuss-style fisherman, perhaps the Cat in the Hat, dandling a brain-rot lure as a Dr. Seuss fish leaps out of the water, grinning idiotically while I’m thinking “This is not how I meant to begin a December 4 column on Franz Kafka; no, this is not what I meant to do, not at all, not at all.”

The epigraph comes by way of the first Arts page in Monday’s New York Times. At least once or twice every year, the Newspaper of Record throws out a line that hooks me. Picture a Dr. Seuss-style fisherman, perhaps the Cat in the Hat, dandling a brain-rot lure as a Dr. Seuss fish leaps out of the water, grinning idiotically while I’m thinking “This is not how I meant to begin a December 4 column on Franz Kafka; no, this is not what I meant to do, not at all, not at all.” The day after I wrote an article on Elon Musk referencing his first and foremost “life lesson,” that “empathy is not an asset,” the New York Times came up with a front page that instantly connected with my post-election state of mind. Lead head: “Chop First and Fix Later: How Musk Tames Costs.” The story directly beneath: “Trump Stands by Defense Pick Who Denies Sex Assault Claim.” Directly under that: “Robots Still Lack Human Touch in Warehouses.” And just below came two smaller heads previewing stories in the Business section: “Social Media Veers Right” and “Spirit Files for Bankruptcy.”

The day after I wrote an article on Elon Musk referencing his first and foremost “life lesson,” that “empathy is not an asset,” the New York Times came up with a front page that instantly connected with my post-election state of mind. Lead head: “Chop First and Fix Later: How Musk Tames Costs.” The story directly beneath: “Trump Stands by Defense Pick Who Denies Sex Assault Claim.” Directly under that: “Robots Still Lack Human Touch in Warehouses.” And just below came two smaller heads previewing stories in the Business section: “Social Media Veers Right” and “Spirit Files for Bankruptcy.”