Voices in Time — A May 7 Gathering

By Stuart Mitchner

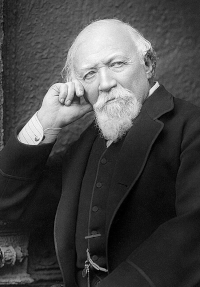

Robert Browning

After looking for poetry in actors last week, I’m thinking of a poet who was a compelling actor in his verse and happened to be born on this day, May 7, in 1812. I formed the habit of reading Robert Browning in lonely motel rooms when I was covering college English departments for W.W. Norton in the mid-sixties. My reading companion was the Norton Anthology of English Literature at a time when Norton’s compact anthologies of English and American lit were being adopted by English Departments from the southland to the heartland. Since I was living on an expense account, most of my salary was going toward a trip to India.

Otherwise, I spent my motel life writing a novel narrated by a fantasist obsessed with Browning. Besides filtering semblances of the master into the twisted prose style of my narrator, I read the dramatic monologues aloud, with gusto, especially my favorite “Fra Lippo Lippi,” all 392 lines of it. You can hear James Mason read the whole thing online. It’s magificent, a one-man opera, every nuance, every smirk, every suggestive snort right down to the nightcrawling painter’s farewell: “Your hand, sir, and good-by: no lights, no lights! The street’s hushed, and I know my own way back, Don’t fear me! There’s the gray beginning. Zooks!”

Reading for Edison

On Browning’s birthday, April 7, 1889, the first recording ever made of a poet reading from his work was barely underway when Browning forgot his lines: “I’m terribly sorry, but I cannot remember my own verses!” Raising his voice in a transatlantic salute to the wizard of Menlo Park and his “wonderful invention,” the old poet declared it a moment he would remember all his life (he had less than a year to live), shouting his name for the ages — “Robert Browning!” — before bellowing three times at the top of his lungs, “Hip-Hip Hooray!”

When a group at Edison’s Menlo Park lab listened to the cylinder recording on the first anniversary of Browning’s death, December 12, 1890, someone suggested that this was the first time any voice had been heard from “beyond the grave.”

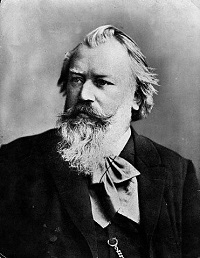

Along Comes Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Born 21 years after Browning, May 7, 1833, Johannes Brahms caught up with the poet at the finish line on December 2, 1889 in Vienna, when an Edison representative recorded him playing what may have been a Strauss waltz, except that, like Browning, he was so excited that he forgot what he was supposed to play. In the end, again like Browning, he resorted to shouting his name, “Herr Doktor Brahms!” The sound of a piano can be heard, but as a musicologist put it, “any musical value can be charitably described as the product of a pathological imagination.”

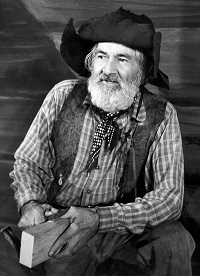

Gabby Hayes in Dubrovnik

Gabby Hayes

On my way west from the trip to India paid for by Norton, I spent two nights in Dubrovnik on the Asiatic coast. It was late May, ten years since the spring of my senior year in high school, an emotional time scored by the “Moonglow Theme” from Picnic, and I was feeling the nostalgia peculiar to memories of home in a foreign land. I had an uncannily clear memory of the streets of the college town I grew up in, reliving the walk to the local movie house where every grade school Saturday I saw cowboy matinees, most of them featuring Gabby Hayes, the fleabitten Falstaff to Hopalong Cassidy’s Prince Hal. Never mind Shakespeare. Gabby’s favorite expression was “yer dern tootin,” and he was a good shot (“I’ll perforate that polecat!”). Most of the kids I knew loved the old guy more than the heroes, Hoppy, Roy Rogers, and smarmy Gene Autry.

So there I was walking around one night in the exotic port where Game of Thrones would be filmed half a century later when I found myself in front of a small movie theater staring at a poster for Heart of Arizona, with Hopalong Cassidy and Gabby Hayes, who, as the mad genius called Coincidence would have it, was born on May 7, 1885. Not that I knew or cared about such things then. It was enough to see the movie. I almost sat through it twice, just like in the old days when my parents had to pull me out by force.

Then Comes Coop

Gary Cooper

It’s kind of a massive anticlimax after Browning and Brahms and Gabby Hayes. But the fact is that on May 7, 1901, Gary Cooper was born. Before I met my wife-to-be a month and a half after Dubrovnik, Coop was a comedian’s “Yep, nope” cliché. I admired him in High Noon and as Lou Gehrig in Pride of the Yankees, but that was it. I discovered the Cooper of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Design for Living, and Meet John Doe when my wife and I began seeing old movies together. One time when we were trying to define what made him so special, even among the stars of Hollywood’s golden age, my wife said “nobility,” and though no one word would do, it was a good start. Now, given where I began last week’s column, I can add “poetry.” That’s the truth behind the man-of-few-words stereotype. Cooper simply does more with less. Poets don’t win Best Actor Oscars, or Cooper would have won for the scene at the end of Frank Borzage’s Farewell to Arms, where he’s eating a brioche, his wife is dying in childbirth, and he’s praying, under his breath.

Admiring Carrie Coon

Carrie Coon

Carrie Coon was born on January 24, not May 7. She’s here because I goofed the spelling of her name in last week’s review (adding an unnecessary “s”), a mistake corrected online but not in print, and I’m glad because it’s given me the excuse I needed to write about an actress my wife and I admired so much in The Leftovers. Certainly poetry had something to do with her unique mixture of force, wit, and charm. We felt about Nora Durst the way you feel about a great character in literature. The character was that rich, full-hearted and forceful, transcending life, death, and improbability, so much so that she above all others gave literary and dramatic credibility to a show that often desperately needed it.

Writing on theringer.com (“In Praise of Carrie Coon”), Lindsay Zoladz mentions the first time Nora’s future lover Kevin Garvey goes home with her. When “two imposing members of the Guilty Remnant cult” standing guard outside her house block the way, Nora grabs a garden hose “and, without a word, sprays down the interlopers at close range.” As Zoladz points out, Nora was “both broken and strong, explosive and contained. Feelings moved through her fluidly but she stayed as rooted to the earth as an old tree.” Zoladz also quotes Fargo 3’s creator Noah Hawley on Coon’s ability to “scramble gender stereotypes,” a “big reason why he cast her as police chief Gloria Burgle. “I needed someone who could play a female Gary Cooper type.”

That sounds like a casual remark, but it’s actually a tremendous compliment.

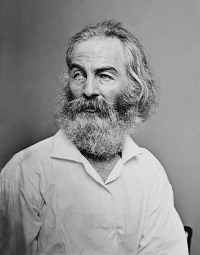

Walt Nails It

Walt Whitman

There appears to be some doubt that Edison recorded Walt Whitman, who was born at the other end of May in 1819. Somehow Edison’s people managed to record Browning in London and Brahms in Vienna, but couldn’t make it downstate to Camden? You can hear for yourself on YouTube. The poet and the composer falter a bit and end up more or less shouting their own names. Leave it to the greatest of all actor-poets to cut through the Edison cylinder surface noise with words that still ring clear today, from “America” (1888): “Centre of equal daughters, equal sons, All, all alike endear’d, grown, ungrown, young or old, Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich, Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law and Love…”

The Poetry of the Gallop

I neglected to mention that the poem Browning was reading for Edison (“How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix”) begins with a gallop: “I galloped, Dirck galloped, we galloped all three.” If you grew up watching Hopalong Cassidy, you’ll know what I mean by the poetry of the gallop. I experienced that music again last night watching Heart of Arizona on YouTube. Close your eyes and it’s one long dusty melodious medley of horses hooves. Let Browning say it: “Not a word to each other; we kept the great pace, Neck by neck, stride by stride, never changing our place….”