Art

caption:

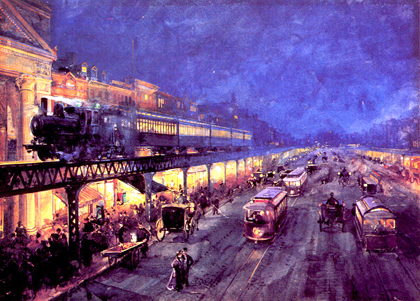

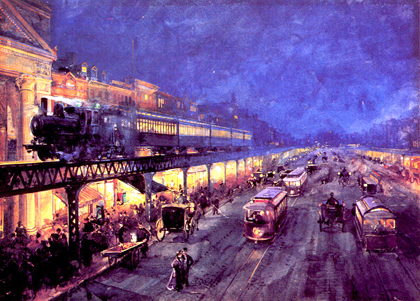

BERLIN'S BOWERY: Irving Berlin began his career as a singing waiter at the Pelham Café on the Bowery. The Michener exhibit, "Show Business: Irving Berlin in Hollywood," includes "The Bowery at Night" by W. Louis Sonntag, Jr., painted in 1895. Also on view is a photo of the Pelham Café, which was known as the "Thieves' Algonquin." Berlin improvised often risqué parodies of the songs of the day, and when two singing waiters from a rival cafe had a hit with an Italian number, Pelham's piano player composed a piece along the same lines for which Berlin wrote the lyrics. It became his first song, "Marie from Sunny Italy," and earned him 37 cents.

|

Marching Up the Avenue With Irving Berlin

Stuart Mitchner

As arranged by guest curator David Leopold, "Show Business: Irving Berlin in Hollywood" at the James A. Michener Museum in Doylestown is the equivalent of a big, colorful scrapbook stuffed with words, images, and music. I hope I'm wrong, but my guess is that the people who come to the exhibit will mainly be card-carrying seniors or movie buffs who already know the great songs of the Porters, Kerns, Gershwins, Berlins, most likely from having seen classic Hollywood musicals like the ones featured in this show. If you want to be cynical, you could say that a museum is the right place for this music. It's been 90 years since Berlin's first big hit, "Alexander's Ragtime Band," swept the nation. So is this music dated? All I know is that when I left the museum I was practically marching in step with that song, and by the time I got to the car I was whistling "There's No Business Like Show Business." Regardless of their age, Berlin's signature anthemic songs still communicate the sort of spirited energy that makes you want to join a parade. He's generally considered the Great American Songwriter ("Irving Berlin is American music," Jerome Kern once said) because of national landmarks like "White Christmas," "Easter Parade," and "God Bless America."

What ultimately makes this exhibit more than a glorified collection of memorabilia (facsimile scripts, letters, drafts of lyrics written on postal telegraph forms and hotel stationery, movie posters, sheet music) is the presence of the music itself in the form of film clips continuously running on a wide-screen television monitor.

The Show Comes to Life

The James A. Michener Art Museum is located at 138 South Pine Street, Doylestown. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday, noon to 5 p.m. Admission for members and children under six, free; general admission $6.50, student (with current ID) $4, senior citizens age 60 and older $6. There is a $4 charge for this exhibition in addition to regular admission.

After touring the rooms, which are divided according to time-periods, beginning with 1888 to 1926 (the composer died at 101 in 1989), I sat down in front of the television monitor thinking I might watch one or two of the clips of scenes from various movies featuring Berlin's songs. I was still sitting there nine numbers later and would have stayed for more if not for the prospect of a long, rainy, rush-hour drive back to Princeton. A clip from the 1937 film On the Avenue shows Dick Powell in his cherubic pre-hard-boiled-private-eye period crooning "I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm," one of my favorite Berlin songs, at least when it's sung by someone who can deliver its rousing, joyous, the world-is-my-oyster enthusiasm. Unfortunately, Powell is too busy handing his evening outerwear to his valet ("Off with my overcoat, off with my gloves") to put it over. The song needs a singer like the young Ethel Merman, who takes "rousing" to another level in the next clip as she belts out the title song from Alexander's Ragtime Band (1938) at the center of one of those classic, extravagantly staged Hollywood fantasies. Better yet is the usually brash and brassy Betty Hutton softly, almost shyly, rendering "There's No Business Like Show Business" from Annie Get Your Gun (1945). Though she begins in a whisper, soon enough she's doing full-throated justice to this typically up-up-up-upbeat celebration of its subject; if there was such a thing as a show biz army, this is the song the troops would sing. Another Betty Hutton gem from the same movie is "Doin' What Comes Nat'urly." In a photocopied letter on display, Berlin recounts the time he told Oscar Hammerstein he doubted he was up to writing the "hillbilly lyrics" required for Annie Get Your Gun, and Hammerstein told him "All you have to do is drop the 'g's." Later that night Berlin wrote, "Doin' What Comes Nat'urly."

The "Couple of Swells" number shown at the Michener, in which Judy Garland and Fred Astaire are vaudeville tramps who can't afford to "drive" or "sail" or "ride" up the Avenue ("so we'll walk up the avenue, yes we'll walk up the avenue"), was so charming I wanted to see it again (as the chorus builds from "walk" to "walk," the two bums strut: it's another spirited Berlin march). So I checked out the Princeton library's DVD of the musical, billed as Irving Berlin's Easter Parade (1948). Among the special features of this edition is a documentary on the making of the movie that shows just how "big" Berlin was and why his name is above the title, a privilege usually reserved for elite directors. One advantage of the DVD is you can do what the museum does and jump from song to song, number to number, without having to sit through all of Easter Parade, which lacks the class and sparkle of a great Berlin/Astaire/Rogers showcase like Top Hat. An additional feature shows Judy Garland singing one take after another of a whimsical number called "Mr. Monotony" that was eventually dropped from the final print in spite of Garland's heartfelt performance. Lines like "Any pleasant interlude that would mean a change of mood/Didn't go with Mister Monotony" and "Sometimes he would change the key/ But the same dull melody would emerge from Mister Monotony" reflect the composer's awareness of the key element that makes his music the antithesis of monotony. Another Berlin song, "He Ain't Got Rhythm," delivers the same message; without rhythm, he's "the loneliest man in town." Berlin began as a singing waiter, after all, moving as he sang; according to a fellow employee quoted in Philip Furia's biography, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song, "he'd keep moving around easy, singing all the time" and "every time a nickel would drop he'd put his toe on it and kick it or nurse it to a certain spot." Even before he was writing songs, it seems that Berlin's gift for rhythm paid off, and when he brought together ragtime and marchtime a few years later in "Alexander's Ragtime Band" (1915), the payoff was enormous: it proved to be the biggest hit in musical history up to that point, the first of 35 number one hits from a man who could neither write nor read music and ended up composing (or at least copyrighting) 899 songs.

One of the numbers shown on the Michener monitor features the composer himself singing in his hoarse tenor "Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning" from This is the Army (1943). It's a touching, almost Chaplinesque performance. Berlin has one of those voices that becomes charming simply by virtue of its humility, a quality apparently not limited to his abilities as a singer. For all his renown as a master of the art of songwriting, he was acutely sensitive to criticism. He almost trashed "There's No Business Like Show Business" when he tried it out on a colleague (Josh Logan) whose silence he misread as indifference. On display at the Michener is a photocopied letter from Oscar Hammerstein describing Berlin's manner when trying out a new song: he was "so nervous and excited… that he fell off the piano stool twice — got so out of breath he had to stop in the middle of a couple of songs to keep from, choking."

Oscar Hammerstein was only one of the American musical theatre legends who resided in Bucks County. In fact, there's actually a Berlin/Michener connection. Irving Berlin's theme song for the movie of James A. Michener's novel Sayonara was the last film work he was to do.

Return to Top | Go to Auto Review