Note: The piece referred to here, "Coal Train," appeared in two parts in The New Yorker, October 3 and 10, 2005.

Consider this might-have-been story line: a banker's son from the midwest comes to an Ivy League school in the 1960s, achieves unparalleled basketball stardom, is a Rhodes scholar, plays pro ball on a championship team, enters politics, is elected senator, elected president, and in 2005 we're not in Iraq and we're not in debt.

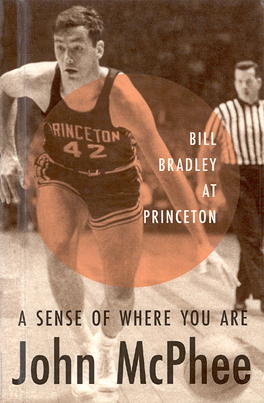

John McPhee's A Sense of Where You Are: A Profile of Bill Bradley at Princeton (the revised edition available for $12 in a Farrar, Straus and Giroux paperback) illustrates the qualities that make the storyline credible as well as the virtues that would have worked against Bradley's achievement of the ultimate goal. It's probably too easy to say that his decency got in the way, but given the nature of the Democratic primary process, it had to have been a factor. While the Princeton hero described by McPhee might have felt the requisite "fire in the belly" when the game was on the line, he was more often the consummate team player, as brilliant and motivated a passer as he was a shooter. Even his sportsmanlike attitude (referees respected him) could be read as a political liability. No showing off, no glory-mongering, no compulsion to become his own lobbyist. Still, you have to think that if the person the book describes had fathomed the political realities and the game of presidential politics as fully as he did the conceptual and practical realities of the game of basketball, a President Bradley might be in office now.

One quality that distinguishes McPhee as a writer is his ability to absorb himself in his subject. He not only has a sense of where he is comparable to Bradley's in relation to the goal, he knows his place, coming across as both the interested, respectful outsider and the companionable listener able to make himself intelligently at home in just about any environment he enters.

If you've been reading John McPhee's recent pieces in The New Yorker you may have noticed the special feeling he has for the west and middlewest: whether he's on a barge on the Illinois River or on a coal train in Nebraska, this Princeton native is clearly comfortable with the "heartland." And his interest in that region might well have originated with his first impression of Bill Bradley's hometown, Crystal City, Missouri. My guess is that most New Jerseyans who think of the former senator as one of their own have either forgotten or don't know that his roots are in a small town south of St. Louis.

Forty years later, A Sense of Where You Are could serve as a title for the body of McPhee's work. One of that book's most remarkable qualities is the way it reveals the writer developing his own sense of where he is and where he has to be as he studies and manipulates, learns from and simply hangs out with his subject. The title phrase refers to Bradley's uncanny grasp of his place in relation to the basket, which enables him to hit a seemingly blind, over-the-shoulder shot observers might think "has the essential characteristics of a wild accident" — "until they see him do it three times in a row." As he explains his ability to hit the basket without looking at it, Bradley gives the author his title: " When you play basketball for a while you don't need to look at the basket when you are in close,'" he says, throwing the ball over his shoulder and right through the hoop. " You develop a sense of where you are.'"

Again, this same phrase can be adapted to describe the instincts McPhee has made such good use of as a writer. The player's instinct for being in the right place is like a writer's instinct for connecting with the right subject, or the right phrase, or for putting himself in the right place at the right time. To get into the obsessive art of a photographer of trains in his recent piece, "Coal Train," McPhee goes out to the siding with the man and watches him work, the same way he suffers through long waits with train engineers or observes firsthand the art of navigating rivers with barge captains. He enjoys exploiting his role as the outsider, and then catching the reader's attention with the equivalent of Bradley's over-the-shoulder shot, as in "Coal Train" when he goes from likening one yardmaster to a football coach to comparing the man taking over his shift to King Lear: "His hair was a sort of robe — a floor-length white robe." You could put all kinds of wily and with-it observers in the same situation and they might give you a reasonably accurate account of the yardmaster's environment, but it's unlikely they'd make so extreme a connection, and even if they did, there's a fair chance it would read more like a "wild accident" than a natural expression of the author's range of reference. Swish! right through the net.

Just as Bradley the player could be described as both imaginative and pragmatic, you could say the same of McPhee. When Bradley misses one jump shot after another during a practice session in the Lawrenceville School gym, he matter-of-factly tells McPhee that it's because the basket is an inch and a half low, the writer goes back to the same gym a few weeks later armed with a steel tape measure, borrows a step ladder, measures the height of the basket, and finds that it's about an inch and one-eighth too low. Another neat move for the author-player, who, in effect, drove with the issue and scored. The same instinct comes into play again on the subject of Bradley's remarkable vision, and this time the author actually manipulates his subject to help make a point: he takes Bradley to a Princeton ophthalmologist. This version of the vision question involves the player's ability to know not just where he is but where his teammates are so that he can pass the ball to them and know they'll be there in time to catch it. When an ordinary player makes such a pass, it's called a "hope pass." Sure enough, Bradley is shown to be 15 degrees above perfection in his peripheral vision and almost 40 degrees above perfection in his ability to see "upward," which, as McPhee points out, is why he's able to "stare at the floor" while waiting "for lobbed passes to arrive from above." Another long shot sunk by the writer, and not on a "hope pass." I wonder if any sportswriter ever had the nerve to take the great hitter Ted Williams and his beyond-perfect vision to an ophthalmologist.

The McPhee Touch

This writer ultimately transcends the basketball analogies, much as the title phrase itself does. Unlike the shoot-from-the-hip wordslinging in Tom Wolfe's early essays or in the work of Hunter Thompson, McPhee's effects can be quiet, sometimes all but invisible. In fact, he supplies a metaphor for this aspect of his style in the second installment of "Coal Train." Describing the subtle descent and ascent the train passes through, he writes that the "significant grades along the way ... reminded me of fish in a river. I couldn't see them." If you're reading too fast you might miss the beauty of an analogy that also nicely demonstrates what McPhee is able, often equally invisibly, to achieve.

By now you may be able to tell that this review was inspired more by John McPhee's work in those October issues of The New Yorker than by A Sense of Where You Are, as good as it is. "Coal Train" is the best thing by any living writer, fiction or non-fiction, I've read lately. It sings with American names and American character, and it makes you feel good about the country again, which is something to be thankful for at this dark period in its history.