Art

|

caption:

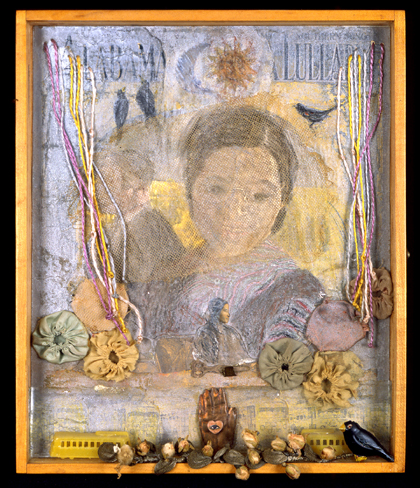

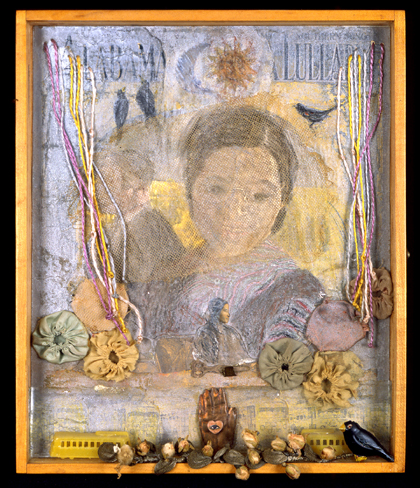

VICTORY OF GENTLENESS (ROSA PARKS): Betye Saar's mixed media assemblage is in a window box against a sheet music background ("Alabama Lullaby"), haunted by the face of the late Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. Co-curated by Judith Brodsky and Ferris Olin, "How American Women Artists Invented Postmodernism, 1970-1975" will be on display at the Mason Gross Galleries in New Brunswick through Friday, January 27, 2006.

|

Triumph Brewery: Women Artists: Up To, Including, and Exceeding Their Limits

Stuart Mitchner

How American Women Artists Invented Postmodernism, 1970-1975" is a title with attitude, one that seems to demand at least an "Oh yeah?" or "Prove it!" from viewers of the exhibit at the Mason Gross Galleries in New Brunswick through Friday, January 27, 2006. Such a title also suggests that the works should be approached according to the terms set forth. For me, the problematic word is "invented." How about "ignited" or "energized," or something closer to "trail-blazing," the adjective used in the press release? The idea that women artists somehow got together and invented postmodernism calls to mind Jelly Roll Morton's notorious declaration that on such and such a day in 1902 he "invented" jazz.

My only issue with a show where the title states an opinion as if it were fact is that it might get between me and the art. As a result, my instinct is to ignore the "isms" and the accompanying information and look at the art as art rather than as a collection of evidence arranged to validate the title statement. It's a debate I'd prefer not to enter, especially since my knowledge of the development of postmodernism is limited.

I should say at the outset that no one who comes to the Mason Gross Galleries is going to be bored. The exhibit has been imaginatively organized by Judith Brodsky and co-curator Ferris Olin, who sees the event more as a "celebration" of women artists than as a testimonial to the inventors of a movement.

As hard as I tried to avoid thinking of the art as evidence, however, there was no way to tune out the background audio from Martha Rosler's performance video, Semiotics of the Kitchen, in which she displays and identifies various mundane kitchen utensils while speaking in a desultory monotone. The effect is that of being followed around by the voice of a sedated Martha Stewart intoning an inventory of functional domestic trivia, including a hamburger press, ice pick, and juicer. If you happen to be a postmodern househusband, you may think "been there, done that" until you glance at the video, notice the date (1975), and observe that Rosler's way of demonstrating the function of the ice-pick is to make a weapon of it, stabbing the cutting board as if it were intimately connected to whoever confined her to this culinary prison.

The voice of feminism also follows you around the adjoining room as Martha Wilson uses various makeup techniques to form and deform her own face in Deformation, another video performance from 1975. Again, it's as if the text inherent in the exhibit's title is echoing in your ears as you stand in front of works like Faith Ringgold's charmingly giraffish life-size soft sculpture, Wilt Chamberlain, or Sylvia Sleigh's not so charming painting of a male nude lounging in a centerfold pose. It's as if I'm being prodded to read the playful depiction of a basketball superstar as a feminist critique of male power, and then to state the obvious about the sex object role reversal in the other work.

What it comes down to is the difference between art as a text, or the illustration of a text, and art as art. The primary value of Sleigh's male nude is as a text. When you see it, you think "Oh, right, it's a feminist art show." When you see Joan Semmel's oil on canvas of two nude bodies stretched out side by side in bed, male and female, large as life (Antonio and I), you don't think about a text. Instead of a cynical response to the well-known male chauvinist stereotype popularized decades ago by magazines like Playboy, you see a formally powerful, strikingly executed work, where the depth and vibrancy and unexpectedness of the colors bring both bodies into a third dimension and give the piece its own special beauty even as it implicitly challenges by example the same stereotype of female sexuality.

Another example of text contending with art is in the same room where you have Joan Snyder's two lively and in no way explicitly or even implicitly "female" oils on the wall to your left facing a gloppy brown mess that seems to have landed splat in the middle of the floor; in fact, it's a bronze by Lynda Benglis that, according to the posted commentary, "breaks with the phallic monumentality" of sculpture. This rationale for its presence inevitably stresses the "ism" and "ist" element of the show. And when you look up from this congealed puddle of matter, there's the television monitor with Martha Rosler demonstrating the function of a juicer as if she were wringing someone's neck.

The Living Text

Carolee Schneemann comes closer than anyone else to bringing the message of the show to life. She puts her body on the line, literally. Both object and artist, she's a self-portrait in progress. To the defenders of aesthetic decorum she's almost as notorious as Robert Mapplethorpe. In the mid-1970s when she was giving the performances shown here on film, she must have embodied the threat represented by Women's Lib: liberation in action, the naked artist spinning in a harness, crayon in hand, turning and twisting on her own version of a high-wire, gymnast, exotic dancer, human sculpture, hypnotist, fantasist, filmmaker and editor all in one. It makes some kind of sense that to see her you have to stray from the show proper. You might miss her altogether or mistake the entrance to her personal theatre for the door of a closet (you have to pass a fire extinguisher and a storage room to get there). You'll know you're there when you see the sign warning you that the video in the next room contains "explicit sexual imagery."

Go through the door and you find yourself in a dark room watching a film Schneemann put together from half a dozen different performances. Unlike Interior Scroll -- The Cave, the explicit video the sign warns you about, Up to and Including Her Limits is muted and dreamlike, the woman's body hypnotic as it sculpts its movements into a slow-motion dive through a soft-focus haze of varying shades of violet and blue against a background soundtrack of seemingly random noises that seem both ominous or mundane: a baby crying, chains or ropes creaking, perhaps the sound of the rope sustaining the harness she's performing in. At first I thought she was playing out the concept of a woman in chains bravely creating, marking the walls of her prison the way a prisoner might mark the days to be served. Perhaps the enchained aspect of the image is meant to suggest the limits she cites in her title. While Interior Scroll is not for the squeamish or prudish, Up to and Including Her Limits should not be missed.

June Wayne's Tapestries

That Carolee Schneemann is an innovator goes without saying. The same can be said of June Wayne, whose career both nourished and was nourished by the feminist movement, which she actually anticipated. In the 1960s her Tamarind Lithography Workshop became one of the most important focal points of a general revival of printmaking in the United States. When you see her two tapestries, however, you don't think about texts or postmodernism or innovation or even invention. You don't think, period: you feel. Although I know what Wayne means when she says that we should "read" tapestries and "eat" art, these two works offer more than either of those terms suggests; whether you consume them or comprehend them, they are magnificent. Col Noir and Onde en Folie were both woven in 1972 at the Atelier de Saint Cyr. While the tapestries far exceed their role as illustrations of the exhibit's theme, they can also be appreciated as significant examples of the idea of woman's work and the weaving associated with the domestic arts through the ages. June Wayne has described the thread as "a basic element akin to the musical note ... a module of construction and a marker for time passing." In Col Noir the thread leads into a fascinating landscape framed in red, with a depths of yellow and gold like pocket canyons below a blue horizon, above it a formation that you might imagine to be (as I did) an abstraction of birds in flight; in fact it's the genetic code, the subject, essence, and signature of the work. For this artist, the text both comprehends and transcends gender, and the ultimate message is art.

"How American Women Artists Invented Postmodernism, 1970-1975" is the inaugural exhibition in a nationwide series, "Indelible Marks: Framing Art and Feminism." The series of exhibitions and events, continuing through 2008, will celebrate the stature and increased visibility of art by women in America.

The Mason Gross Galleries are located at Civic Square, 33 Livingston Ave., New Brunswick, in Rutgers' Mason Gross School of the Arts. The galleries are open Monday through Friday, from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., and by appointment.

Return to Top | Go to Auto Review