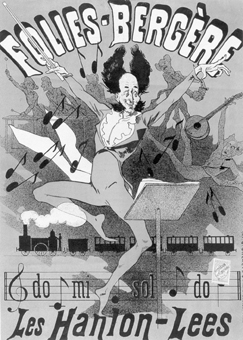

Art

INTOXICATION: Jules Chéret's antic lithograph for the Folies Bergère puts mania to music in the Voorhees Special Exhibition Galleries at the Zimmerli where the exhibit titled "Toulouse-Lautrec and the French Imprint" could just as well be called Poster Mania ("L'Affichomanie"). Billed as the largest and most comprehensive exhibition to date dealing with French posters and their influence from the early nineteenth-century Romantic period to Art Nouveau, it will run through February 17, 2007. The museum is located at 71 Hamilton Street on the College Avenue campus of Rutgers University. Hours are from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesday through Friday, and from noon to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. Admission is $3 for adults and free for museum members, Rutgers students, faculty and staff (with ID) and children under 18. Admission is free on the first Sunday of every month. For more information, call (732) 932-7237, ext 610.

|

Baudelaire, Poster Mania, and the Poetry of the Street

Stuart Mitchner

How odd, to have the place all to myself on a Saturday afternoon. It’s a bit gloomy and Novemberish outside but in here a mere 15 miles from Palmer Square it’s a sunny, windy day in Paris in 1898, I’m at the top of the city, Montmartre, the Moulin de la Galette, where the wind’s blowing so hard the men have to hold hard to their hats and the women their skirts, and the blades of the windmill are spinning like the logo for an advertisement come to life, like one of those animated sky-signs that used to delight the eye in the old Times Square. Look down and all around for as far as you can see, it’s a drunken dream of Paris — the metropolis half-submerged in a sea, or a vast mirage of wavy, choppy blue water, with Notre Dame looking like a mirage itself, its two towers mere shadows, and jutting into view on the other side of the the city, the brand-new Eiffel Tower. And beyond it all, the soft pastel shade of the sunset makes a pleasing contrast to the bolder color of the lettering.

The lettering?

In fact, this vision really is an advertisement splashed across a poster that once covered a wall, not in a museum but in the street with all its passing crowds, noise and dirt, wind and rain. Georges Redon’s immense lithograph publicizing the Montmartre dance hall/cafe is almost the first thing you see when you walk down the steps into the show that just opened in the Voorhees Special Exhibition Galleries at the Zimmerli. The exhibit is called “Toulouse-Lautrec and the French Imprint,” but it could just as well be titled with the phrase that turns up more than once on placards throughout the exhibit: Poster Mania (L’Affichomanie) starring Toulouse-Lautrec. The idea of a headliner makes perfect sense given the nature of the show. A household word like Lautrec is far more likely to sell the product than Jules Chéret or Eugene Grasset or Bertall or Cazal or Steinlin or even Alphonse Mucha.

The subtitle is “Fin-de-siècle Posters in Paris, Brussels, and Barcelona,” but the other cities play only a small part in a show thoroughly dominated by the vast city delineated in Redon’s poster. Their primary role is to demonstrate how far the mania had spread.

Baudelaire

Baudelaire could have written a fascinating essay on L’Affichomanie. Right now he’s staring up at me from a book of his writings, the cover photograph by Étienne Carjat. This is the man who supposedly once told a waiter to bring him a steak “as tender as the brain of a newborn infant,” the man who wrote that “laughter is satanic” and “is thus profoundly human,” though it’s hard to imagine this rigid, thought-worn face ever breaking into a smile, let alone giving way to laughter. No doubt because I’ve been reading his essays, I found intimations of Baudelaire all through the exhibit. Never mind that he died decades before the turn of the century, he’s very much present in a Jules Chéret poster from 1889 adjacent to Redon’s sprawling cityscape: an advertisement for Le Rire, the journal that printed illustrations by Lautrec and some of the other artists on display here. Replete with death’s heads, sinister clowns, and the large laughing face of a creature you wouldn’t want to meet alone in a dark alley, the image’s nightmarish notion of laughter evokes another sort of mania, like the one Baudelaire described in his essay on the subject: “At once a dizzy intoxication is abroad; intoxication swims in the air; we breathe intoxication; it is intoxication that fills the lungs and renews the blood in the arteries.”

Over here at 42 Boulevard Bonne Nouvelle just a few steps away from Le Rire on 10 Rue St. Joseph (the addresses on the posters help encourage the illusion of a walk through Paris streets), there’s a subject for a Baudelairean prose poem out of Paris Spleen. It’s a poster for an exposition of “des Arts Incoherents,” the red lettering capering on spindly marionette legs like those of the Pierrot who inspired Baudelaire’s riff on intoxication. And what better illustration for “incoherent” art than the face of a circus clown, one of the primal images of the grotesque — the horror on the other side of laughter.

Think of the flights or descents these visions from the city walls and streets might have inspired in the author of The Flowers of Evil. Again, though he died years before the mania reached its highest pitch, he seemed to see the poster phenomenon coming in essays like “The Painter of Modern Life,” where he celebrates the caricatures of Daumier and Gavrani, and the idea of art and poetry inhabiting and illuminating the life of the street. When describing the unheralded, deceptively modest drawings of Constantin Guys, he’s paying tribute to the artists of “everyday life” whose work either could not be found in the Louvre or else would be ignored by people making a beeline for certified deities like Titian or Raphael. He also understood the “mixed nature” of artists who are not concerned with subjects like history or religion but who have “a kinship with the novelist or the moralist … the painter of the occasion and also of all its suggestions of the eternal.”

The combination at work in these images from the Paris streets recalls Baudelaire’s definition of caricature as “a double thing: it is both drawing and idea — the drawing violent, the idea caustic and veiled.” And it’s the idea of art for sale, brought down from the aesthetic heights to specifics of cost, time, and place, the everyday reality documented in the exact price listed for admission to the Exposition of Incoherent Art: only 85 centimes if you go on a Sunday. In 2006, if you want to actually buy that poster, you can get it from an online gallery in Geneva for anywhere from $700 to $1700. Still, that price range is at least within reason. One of the virtues of poster art is its relative affordability.

Offbeat Lautrecs

With the show’s headliner, you realize just how thoroughly his art has entered the everyday. If Lautrec is a household word (at least in the homes of the educated classes), his posters are household works. You know as much when you see the patently familiar images: Jane Avril, Yvette Gilbert, La Golue, the dancers at the Folies. Or take posters like the one advertising Aristide Bruant’s debut at his own cabaret: you’d might not know the name but you’d recognize the image the instant you saw it because at one time or another in your life you’ve seen it in a cafe (like the Lautrec on the wall of the Parisian-style cafe at Bon Appetit in the Princeton Shopping Center) or a dorm room or a living room. For that reason, you may be drawn to darker Lautrecs like the two illustrations he did for Fin-de-siècle equivalents of policiers like Le Pendu, where the hanged man is being discovered with a candle, a stark image worlds away from the high-kicking dancers of the Moulin Rouge (though Baudelaire would probably discern a comic/satanic connection between the dance of life and the involuntary kicking of the suspended corpse). Then you have the doomed man approaching the guillotine with a formation of mounted soldiers in black ranged in the background in At the Foot of the Scaffold, which is advertising a memoir in Le Matin by the Abbé Faure, a witness to 38 executions.

There are shadows even in the brightest, flattest, and most Japanese of Lautrec’s posters. In the most familiar of them all, the one advertising the Moulin Rouge, our view of the dancer La Golue is shadowed by a grotesque figure in the foreground and the pitch-black silhouette of the watching crowd that is drawn every bit as darkly as the line of mounted soldiers in At the Foot of the Scaffold. There is something broadly sweeping and free in Lautrec that sets him apart. More than anyone else in the exhibit, he seems to be challenging the limits, as can be seen in the famous poster of Jane Avril from 1893 advertising a cafe concert at the Jardin de Paris. The dominant image is not the dancer but the huge, disembodied hand of a musician in the foreground clutching the top of a bass viol.

From Beer to Sardines

Quite a range of products being sold in this show: beer (the oldest ad, dating from 1815), ink, bicycles, clocks, champagne, petrol, gloves, novels, Mexican chocolate, Dubonnet, newspapers, plays, matches, places of amusement, ice palaces, even sardines (a fishy, whimsical gem), and automobiles like the Brasier, depicted in an immense poster from 1906 by L. Cappiello that creates green waves of speed around the car, which has a grinning demon at the wheel. Baudelaire would love it. Call it mania or intoxication. Emerson would probably agree. He knew a thing or two about signs: “The schools of poets and philosophers are not more intoxicated with their symbols than the populace with theirs …. Some stars, lilies, leopards, a crescent, a lion, an eagle, or other figure … on an old rag of bunting, blowing in the wind, on a fort, at the ends of the earth, shall make the blood tingle under the rudest or the most conventional exterior. The people fancy they hate poetry, and they are all poets and mystics!”

Return to Top | Go to Book Review